What has pushed me to patiently chronicle this history is: [to rebut] those who identify themselves as “PFDJ”, family or others, specially those who, wherever you settle in a new land conduct the interviews, and claim that the life we experienced is a lie, and that “it’s easy [compared to the hardship] that others have passed through, why are you turning against your country.” Because of this [attitude], many of our co-strugglers have been told “rejected!” [in their asylum-requests], and are wasting away in some countries. This is why I am passionately chronicling history and I invite you to correct my shortcomings in the comments section. Please share with others so it can reach everywhere. I am Yohannes Ahferom “Fabrigas.”

In part 2, I had disclosed that when we returned after burying our comrades, we were met with sad faces. But the Members [the administrators], not only were they not sad, they were surprised by our sadness. Because: if your comrade is sacrificed, you don’t cry, and you are not sad. Their thought pattern is: “he was sacrificed heroically.” It is amazing: to see this in a free country. In our long march, we experienced many hardships.

From my narration in part 2, some of you who were members of my Company have asked me, “when was it that you were ill and had the toothache?” I didn’t write Part 2. It was written by Comrade Musael Temesghen. It is important to clarify: everything must be presented truthfully.

This journey has left a wound that won’t heal on everybody. Most of the Members [administrators] are cruel and have no empathy. There were periods when we couldn’t have water to drink. We have drunk from watering holes of animals. Do you remember of the time our backs were broken? Ughh: It makes you hate being created. But, truly, we are brave: its our love, our unity [that saved us] otherwise it wouldn’t have been overcome. Do you remember the time we couldn’t find shelter to sleep in and the cold weather was impossible to take? When everybody had to dig a hole to sleep in and the useless sheets we were given made us feel even colder. Coupled with the blisters in our feet: it was agony. There were times we used our sisters’ menstrual pads to cover our blistering feet when walking. The pads were really useful.

Anyway, all that passed. And we had arrived at Adiab and Roba Heday [in the outskirts of Afabet.] So how was life at Afabet? Let’s follow this up in Part 3:

When we arrived at Adiab, [we learned] it is an unadulterated desert. Here and there, you may find agricultural and pastoral area. As happy as we were to come to the end of our journey, we were given no shelter, not even tents. Like animals, we just took shelter under the shade of trees. But after a while, one gets to acclimate, and we formed groups of four and five and started building our shelter. The bedsheets used as a roof to shelter us from the sun are brought down at night to be used as blanket to cover us from the cold. And when you awaken in the morning, you erect the bed sheets again. In time, we created our town.

At any time, the presence of females makes life worthwhile. We started decorating our homes. [As the proverb has it]: if you are going to dance, better twist and turn. We acclimated to our life and, truly, when youth join hands, they are industrious. Even in the hard times, there was happiness, stamina and tolerance.

We, boys and girls, slept on one bedsheet, like siblings. Nothing to it; how can you even think about it? As time passed, however, it’s not lost on you what will happen next. Youthful behavior, here and there. But it is not a bad thing; it adds spice to life. Oh, I forgot: baking bread. Most of our sisters had no experience making bread. Sometimes it would burn and sometime it would crumble: it is “wedi Aker” [Sudanese sorghum] grain. Many of our sisters in the 25th and 26th learned how to make bread in Afabet.

What’s amazing to me is the case of the Members [administration.] As if they were their wives, they would critique the female’s baking skills and make them cry. Some of the males had no experience at all with country life and couldn’t do simple tasks like chopping wood. In the beginning, we had to line up to eat. Oh the vigilance required! If a platoon lined up and ate, it would line up again to get second serving. But in time, they changed this to serving by Group. And our sisters started improvising: blending the Sudanese sorghum with bleached wheat to make injera. Even though the outcome wasn’t that good, since it was being prepared in pans and not clay ovens, we nonetheless rushed to consume it. Truth be told, it was also responsible for many experiencing gastritis due to the bread being overcooked.

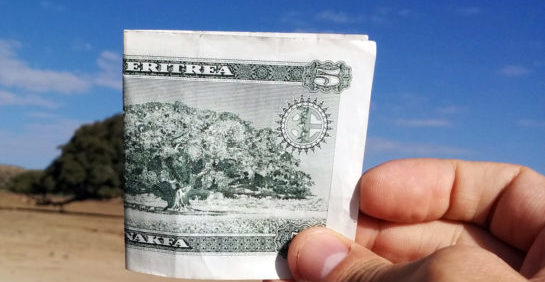

In the beginning, we experienced a lot of undernourishment. Coupled with the cold weather, it was very difficult. We were too many. Each Group (“ganta”) had 90 members. Two meals a day. Noon time [meal], it was either bread with fava beans, or pasta fajioli, and the portions were small: we filled the rest [of our appetite] with jokes and laughter. Two meals was not enough so we used the money we brought from home to buy bread, 5 Nakfa each. Many thanks to the people of Afabet: their kindness, compassion, empathy is indescribable.

In any event, the awful man who announced our journey from Sawa, Brigadier General “Wedi Memher”, showed up at Afabet and called a meeting. Nobody else has his arrogance and cruelty. After greetings, he asked how our journey was. All expressed their displeasure by looking at the ground. And his, “this journey was really easy. Only two of your comrades were sacrificed. We were expecting worse. You are brave: the country is now yours [to protect]. A country that came about through so much sacrifice, you are now the recipients of a trust,…” whatever, blah blah was saddening to us.

Their goal was for all of us to perish. A journey where we buried our comrades, where many of our siblings experienced heart problems, shortness of breath, hemorrhoids, and a journey of agony, he described as an “easy journey.” It is amazing. Our brave martyrs died so we can live in the light, so we can be educated and build a country NOT so we can go through what they went through. A weak leader uses the martyrs as props to cover his weakness: poor martyrs!

No obstacle for a youth, united. But the military teaches cowardice: a platoon fears the platoon leader; the platoon leader fears the group leader; and so on, up the chain, you live cowardly.

The joys of life in Adiab surfaced when, on occasion, we would raise money to buy coffee and popcorn, brew the coffee on kettles and pop the corn in a pot, and drink the coffee using gasoline or tomato sauce cans. We had a good relationship with the 25th Round. Yeah, the 25th: you are so sweet! When we would get together, we were so many.

One day, we had been instructed to go somewhere and bring along our properties. That’s when distinguished instructors and others told us, “you have fulfilled your service. Wherever you attended your last class, you can retake the matriculation exam.” We, misunderstanding what they said, proceed to be joyful, to hug, and to exchange phone numbers. We thanked God.

“My dad and my mom: each has a different prayer,” is what my grandmother used to say. Unexpectedly and in demoralizing move, they separated us from our properties, packs we had brought from home like kerensho [air-dried bread], tihni [flour made of lightly roasted grain], Dilikh [seasoned hot pepper] and others…they confiscated them as bandits would. It is amazing. When this act of banditry occurred in our battalion, we told the two other battalion members to hide their property. I remember everyone digging and burying it in the sand. In any event, stories like that are endless.

Once at Afabet we decided to entertain ourselves by trying to make Dmu-Dmu [high-proof distilled spirits, moonshine.] We baked bread and popcorn, put together a special dance and fashion show, a general knowledge contest, an eating contest, and short comedies. Because that was done in coordination with members of the 25th, we can’t forget it. It was while we were in this relaxing environment that we had a shocking experience.

We were told that within a short period of time, those who are enrolled in certificate and diploma courses would have to leave: we were now as sad as orphans. How are we going to cope without them? We started missing them before they left. It’s tough. We put together a modest farewell party, far less than they deserve. Like a woman who just delivered a child, we kept asking “today or tomorrow” until their day of departure. As they say, “a day and a dog will show up even if you don’t summon them,” the black day of their departure arrived. Everybody was in tears. Even the hardened and cruel Members were touched by our tears. We exchanged phone numbers and whatever rubber was around our necks and hands as memorabilia. There is no choice: bitter as it was we had to be separated. I can’t adequately express the feelings.

After they left, [due to loss of appetite] the nights we went without dinner outnumber those we did. Adiab felt so lonely. Although we were many, we still felt the sting of their absence. For all of the 25th and half of the 26th, thus ended their life at The March. On this occasion, I want to wish peace and good health to all my comrades, wherever you may be. There was no joy after you left; your love is intense. Let’s not forget one another. May God bring forth a time when we visit our home, accompanied by our children. In any event, we could not forget you.

After the 25th and half of the 26th certificate course attendees left, because everybody had bought [music] tapes, wherever you go all you heard was music. It felt like a big town. Although life there wasn’t good, as they say, “on top of what she was going through, she was given bad news”, we were told we were headed to Nakfa. “This is a historic place and we will walk on foot there”, is what they told us. Most of us found this to be a funny statement. We are going to walk on foot, for ten days, to see a historic place? We were amazed. Oh, well, we readied ourselves. Only those who had health issues stayed behind. Those whom they judged to be healthy enough, they said they would have to go with us. The decisions of these people is mind-boggling.

As usual, we got ourselves prepared, pooled money to buy tents. There is no choice. We consoled ourselves “it can’t be worse than the marches we undertook already” and we psyched ourselves to be happy travelers. From Adiab, the Machinery and Commando Battalions, we headed on a 73- kilometer journey to Nakfa. The Agriculture and Officers Battalions had a relatively shorter trek. Starting from Roba Heyday to Nakfa, it was 50 kilometer journey: they had a 23 kilometer head start. The march was tiresome and exhausting. But there was music which made it bearable, and there were musicians, sometimes walking in the opposite direction, just to entertain us.

Thanks to our love and fortitude, we carried what we carried, supported whom we supported, we dragged ourselves to Nakfa. Nakfa met us with its cold weather. Because we arrived at night, it was foggy and misty. We started getting ready to sleep: it was very cold. Eritrean youth means love. The youth attending technical classes there brought us food and drinks. They inquired of people they knew; they met those they could, asked us to pass their greetings to those why couldn’t, and they were directed to leave the place. We hugged lovingly and parted ways. The life of a soldier is incomplete; there is always something missing. The cold whipped us all night, to the point we hated being created and, in the morning, we had breakfast, we headed to the historic place [Nakfa], site of courage and martyrdom. The commander of the division, Merhawi, was the narrator and escort of each historic site. Truly, it is amazing. We are lucky to have witnessed the sites of our fathers. The only question is: how? On a precipice that is frightening just to look at, they had built trenches, committed historic acts and brought about independence and now, we are grateful that they are not witnessing them dragging us around. Because, this unbelievable site, built with an empty stomach, a unquenched throat and a weather beat back was done so we would be more comfortable. Our martyrs have not been compensated for their sacrifice.

In any event, the stories of our martyrs are endless and we returned back to the place we spent the night in. “We are going to get moving; go on and prepare lunch!” is what they told us. We were so hurried, and we rushed to pack our properties, and headed back to Afabet.

We were pleased that we got to see historic Nakfa. But, was it necessary to undertake this long march just to have a one-hour historic site tour? There were so many cars around. But because their plan is to create exodus, we are offending them by even suggesting this idea. We all had thought we would stay in Nakfa for at least three days. We didn’t think it would be a one-hour tour. From Nakfa to Adiab is 73 kilometers. The round trip was 146 kilometers. And for those who started their journey from Roba Heyday, it is 100 kilometers round-trip. In any event, as usual, supporting one another, calling each other my brother and my sister, we endured the journey of fatigue and illness and returned back to our point of origin. Those who had stayed behind had prepared food and drinks for us for our arrival. I remember, like people returning from a wedding, we blasted the music when coming back to our base.

Unbelievable! They exploited the big-heart and innocent youth. We bathed, ate and, because we were exhausted, slept.

Part 4 continues

Leave A Reply